Today's Democratic Socialists Could Learn A Great Deal from the Jamestown Colony

They Starved in the Midst of Plenty

The Common Store - A Failure of Early American Socialism

The wind off the James River in the winter of 1609 carried the smell of death. Inside the palisade of Jamestown, five hundred English souls had dwindled to sixty. Men who once wore velvet doublets now gnawed on boiled boot leather and the bones of rats had abandoned. The granary they called the Common Store stood almost empty, yet the fields around the fort lay fallow. Why plant corn tomorrow, the settlers reasoned, when the corn you plant today goes into the same warehouse that feeds the idler who sleeps until noon?

A gentleman named Wingfield, who had never swung an axe in his life received the same daily pint of wormy wheat as the carpenter who mended the stockade. The blacksmith refused to light his forge because the charcoal he burned and the nails he forged belonged to “the Company,” not to him. Hunger, that sternest of teachers, soon taught them the lesson that no sermon could: when no man reaps what he sows, few men will sow at all.

Captain John Smith stormed through the fort with a drawn sword and a new commandment carved into every heart: “He who will not work shall not eat.” Yet even Smith’s iron will could not break the charter law. The Virginia Company in far-off London had decreed a commonwealth. All labor was to be joint, all reward equal. The result was not equality but universal misery. By spring, the survivors looked like living skeletons, and the Powhatan mocked them as “tassantassas (strangers) who starve in the midst of plenty.”

Only when Sir Thomas Dale arrived in 1611 and committed what the Company’s directors would have called theft did the colony breathe again. Dale took a blade to the charter. He gave every man three acres of cleared land to call his own. Overnight the sluggard became a plowman. Corn sprang up where weeds had reigned. Hogs multiplied. Within six months Jamestown exported food instead of corpses. The same hands that had refused to lift a hoe for the Common Store now worked from dawn past dusk—for themselves and their families. The lesson was brutal and clear: private property turned starving Englishmen into prosperous Virginians.

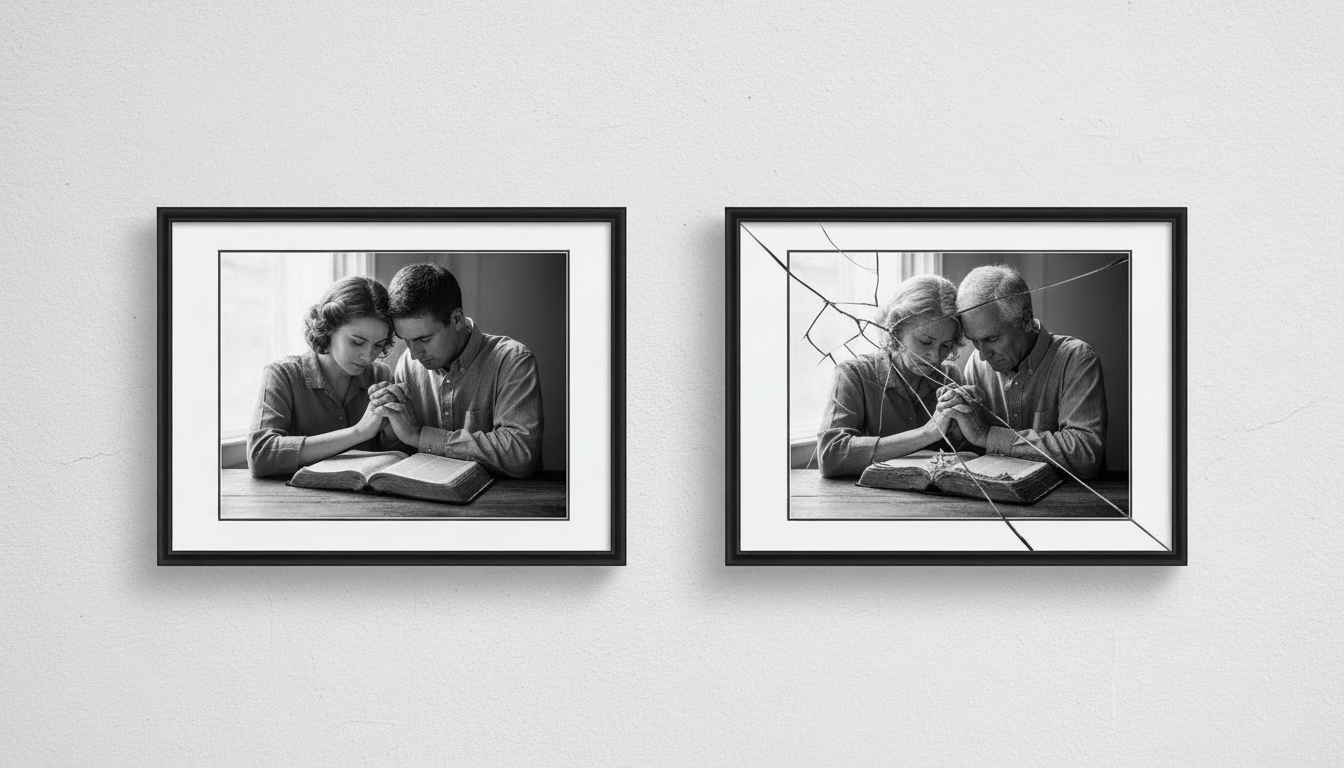

Three hundred and eighteen years later, in the America of 2025, the ghost of the Common Store still walks.

It appears whenever a society decides that effort and reward must be divorced. It whispers through policies that punish the diligent and subsidize the idle, that seize the fruit of one man’s labor to feed another man’s indifference. It manifests in the quiet tragedy of cities where whole generations grow up believing work is optional because the modern common store—welfare without strings, bailouts without reform, student-loan forgiveness without accountability—will always be replenished by someone else’s toil.

In 2025 we do not lack granaries; our silos overflow. Yet in certain neighborhoods the fields of human potential lie as fallow as those around Jamestown in 1609. Young men scroll phones while the Common Store—now wired through direct deposits and EBT cards—provides just enough to keep body and soul together without demanding either body or soul be put to useful purpose. Entrepreneurs hesitate to hire because regulations and tax policies treat profit as a moral failing rather than the signal that a need has been met. The gentleman in velvet has become the trust-fund activist who condemns capitalism from an iPhone assembled by wage earners he will never meet.

The lesson of Jamestown is not that compassion is evil. Ships of mercy did arrive in 1610, and charity saved the remnant. The lesson is that charity and commons are not the same. One is voluntary and temporary; the other is compulsory and perpetual. One preserves dignity; the other erodes it. Jamestown survived only when Englishmen were allowed to own the corn their own hands planted. America in 2025 will thrive—or wither—by the same measure.

The Common Store always begins with the promise of fairness and ends with the reality of shared starvation. The private plot begins with inequality of effort and ends with abundance enough for all. Four centuries apart, the wind off the James still carries the same warning: a society that severs the link between work and reward will, in time, sever the link between its people and their future.