Jánošík Still Rides

Through the pine and the thunder, through the wind that never dies ...

This post is an experiment. I attempted to research a culturally iconic figure and legend from a culture I don't know much of anything about, then write lyrics to a song based on that story. Then ... use tools to translate both the story and the lyrics to the Slovak language and THEN ... produce musical pieces in both languages.

I'm in need of someone who understands the language to tell me just how awesome ... or awesomely bad ... this effort turns out to be.

Posts on this site may contain copyrighted material, including but not limited to music clips, song lyrics, and images, the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. Such material is made available for purposes such as criticism, commentary, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, education, or research, in accordance with the principles of fair use under Section 107 of the U.S. Copyright Act.

Jánošík Still Rides - English

[Verse 1]

Born beneath Rozsutec’s crooked crown, 1688

Shepherd boy with storm-cloud eyes learned the mountain’s ways

They marched him off in Habsburg chains, taught him how to kill

He turned the musket on the lords and ran for the higher hills

[Pre-Chorus]

Silk rope for the wicked, open hand for the poor

Eighteen wild brothers, pistols singing at the door

[Chorus]

Hey-ha! Jánošík still rides!

Through the pine and the thunder, through the wind that never dies

Hey-ha! Death couldn’t hold him down

He laughed on the iron hook while the empire wore a frown

Raise the glass, stomp the floor, let the rafters split wide

For the shepherd turned outlaw: Jánošík still rides!

[Verse 2]

He leapt the gorge on three bent pines, bullets turned to rain

Danced on crags where eagles fear, cloak like a hurricane

Took the gold from velvet throats, scattered it in the mud

For widows in the valley and orphans without blood

[Pre-Chorus]

Betrayed by a kiss of silver, thirty coins that burn

They dragged him down to Mikuláš, thought the page would turn

[Chorus]

Hey-ha! Jánošík still rides!

Hook through the ribs, still laughing, blood like rowan wine

Hey-ha! They couldn’t kill the fire

He sang as the heavens cracked and the hangman retired

Raise the glass, spit on chains, let the night ignite

For the man who robbed the robbers: Jánošík still rides tonight!

[Bridge – slower, almost spoken over fujara wail]

Empires rose and crumbled, statues turned to dust

Kings and commissars promised the mountains would learn to kneel

But every winter wind that howls through Malá Fatra

Carries the same wild laugh they tried to bury in 1713

[Final Chorus – full scream, double-time, whole room roaring]

Hey-ha! Jánošík still rides!

Over Kriváň at midnight when the slivovica flows

Hey-ha! Hear the spurs on the stone

Every child in Terchová feels him in their bones

If your back is bent and the yoke is burning red

Look to the ridge, brother: he’s just ahead!

Hey! Ha! Forever!

Jánošík still rides!

Jánošík still rides!

Jánošík never died!

[Outro – gang-shout, stomping fades into mountain wind]

Valaška high! Heart on fire!

The mountains keep our king!

Hey! Hey! Hey!

The wind howls through the High Tatras like the cry of an eagle robbed of its young, and in that wind the name still rides: Jánošík! Juraj Jánošík! A name that is not merely spoken in Slovakia but sung, spat, wept, and sworn by, a name that cracks like a whip across three centuries and still draws blood from the colour of freedom.

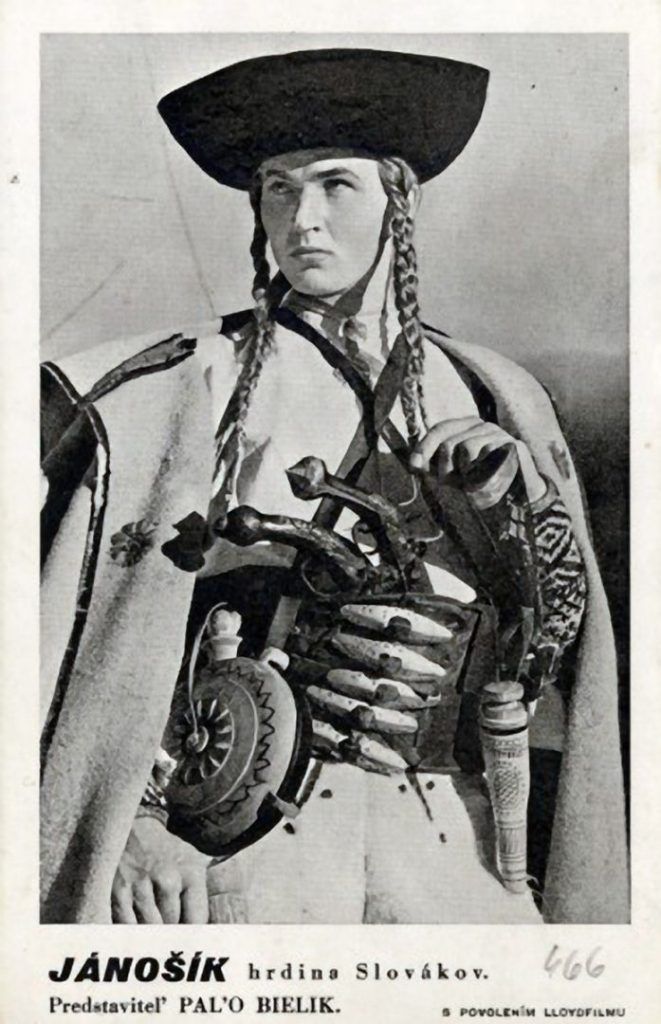

He was born in 1688, in the tiny village of Terchová, under the crooked peak of Rozsutec, where the rocks themselves seem to lean forward to listen. A shepherd boy first, then a soldier in the Emperor’s army, then a deserter when he saw how to load a musket against his own people. The Habsburg yoke pressed down on the Slovak neck like an iron collar, and the Hungarian lords grew fat on the sweat of highland peasants. The law called it order. Jánošík called it theft on horseback.

So he stole back.

With a band no larger than a wedding party (eighteen, twenty, twenty-five men at most) he turned the Carpathians into a fortress and a court of justice. They struck at night, silent as falling snow. A nobleman’s carriage halted on a lonely pass, pistols glinting like wolf eyes, and in moments the gold, the furs, the ducats were gone, scattered among widows and orphans before the sun rose. He never took from the poor. He never harmed women or priests. When he hanged a lord, he hanged him with courtesy: a silk rope, so the neck would not bruise.

They gave him miracles, because a nation in chains needs miracles. They say he could leap from crag to crag like a chamois, that bullets turned to water against his sheepskin cloak, that he once tied three pine trees together with his belt to make a bridge across a gorge. They say when they finally caught him (betrayed for thirty pieces of silver by a false comrade) he laughed as they led him to the hook. Laughed! The executioner drove the iron through his ribs in the square at Liptovský Mikuláš, and Jánošík danced on air, blood bright as rowan berries, singing a hajduk song until his heart stopped.

That laugh is the soul of Slovakia.

For three hundred years the powerful have tried to kill that laugh. Habsburg officers burned the songs. Hungarian gendarmes shot the singers. Fascists hanged new Jánošíks from new hooks. Communists locked the legend in a museum case and called it “class consciousness.” Every time, the mountains gave the laugh back, sharper than before.

Because Jánošík is not a man; he is the refusal to kneel. He is the axe that remembers the tree. He is the shepherd who became a storm. In every village square there stands a statue (valinka hat tilted, pistol in one hand, the other open as if to say: “Take what is yours”). Children learn to walk by holding his stone fingers. Old men toast him with slivovica and swear they saw him last night on the ridge above Zázrivá, cloak snapping in the wind, checking that the rich are still afraid.

He never won a kingdom. He never sat on a throne. He ruled for only three summers, and he died at twenty-five with an iron hook through his side. Yet no emperor, no dictator, no foreign army has ever ruled the Slovak heart the way Jánošík does. Because empires pass like snowmelt, but the man who robs the thief and gives to the robbed, the man who laughs while the hook tears him apart, that man is forever.

Listen on a winter night in the Tatras. When the wind screams down from Kriváň and the fire settles into embers, you will hear it: the faint jingle of spurs on stone, the low whistle of the robber’s song, and then the laugh, wild, defiant, immortal, cutting through the dark like a blade of living light.

Jánošík rides still.

And as long as there is one Slovak who remembers what it feels like to stand straight under a heavy yoke, he will never ride alone.

Cez borovicu a hromy, cez vietor, ktorý nikdy nezhasne...

Tento príspevok je experiment. Snažil som sa preskúmať kultúrne ikonickú postavu a legendu z kultúry, o ktorej takmer nič neviem, a potom som napísal text piesne založenej na tomto príbehu. Potom... použiť nástroje na preklad príbehu aj textu do slovenčiny a POTOM... vytvárať hudobné skladby v oboch jazykoch. Potrebujem niekoho, kto rozumie jazyku a povie mi, aké úžasné je... alebo neuveriteľne zlé... Toto úsilie sa ukáže byť skutočné.

Príspevky na tejto stránke môžu obsahovať chránený materiál, vrátane, ale nielen, hudobných klipov, textov piesní a obrázkov, ktorých použitie nebolo vždy výslovne autorizované držiteľom autorských práv. Takýto materiál je sprístupnený na účely ako kritika, komentáre, spravodajstvo, výučba, vedecká práca, vzdelávanie alebo výskum, v súlade so zásadami spravodlivého použitia podľa sekcie 107 amerického zákona o autorských právach.

Jánošík ešte jazdí

[Verš 1]

Pod Rozsutcom krivým narodený, roku tisícšesťstoosemdesiatosem

Pastierik s očami búrkovými učil sa od hôr

V habsburských reťaziach ho viedli, učili zabíjať

Otočil mušketu na pánov a utiekol do vyšších vrchov

[Predrefrén]

Hodvábne lano pre zlých, otvorená dlaň pre chudobných

Osemnásť divokých bratov, pištole spievajú pri dverách

[Refrén]

Hej-ha! Jánošík ešte jazdí!

Cez borievie a hromy, cez vietor, čo nikdy neumrie

Hej-ha! Smrť ho neudržala

Smial sa na železnom háků, kým sa ríša mračila

Zdvihni čašu, dupni do zeme, nech sa trámy lámu

Za pastiera-zbojníka: Jánošík ešte jazdí!

[Verš 2]

Tri borovice ohnul cez roklinu, guľky sa menili na dážď

Tancoval po skalách, kde sa orol bojí, plášť ako hurikán

Zlato bral z hodvábnych hrdiel, rozhadzoval po blate

Pre vdovy v dolinách a siroty bez krvi

[Predrefrén]

Zradili ho bozkom strieborným, tridsať grotov žeravých

Vliekli ho do Mikuláša, mysleli, že sa strana obráti

[Refrén]

Hej-ha! Jánošík ešte jazdí!

Hák cez rebrá, stále sa smeje, krv ako jarabina

Hej-ha! Oheň nezhasili

Spieval, až sa nebo roztrhlo a kat odišiel do dôchodku

Zdvihni čašu, pľuj na reťaze, nech sa noc vznieti

Za muža, čo okrádal zlodejov: Jánošík jazdí ešte dnes v noci!

[Bridge – pomalšie, takmer hovorené cez kvílenie fujary]

Ríše sa zdvihli a rozpadli, sochy obrátili na prach

Cisári aj komisári sľubovali, že hory sa naučia klaňať

Ale každý zimný vietor, čo vyje cez Malú Fatru

Nesie ten istý divoký smiech, ktorý chceli pochovať v roku 1713

[Posledný refrén – plný rev, dvojnásobné tempo, celá krčma reve]

Hej-ha! Jánošík ešte jazdí!

Nad Kriváňom o polnoci, keď tečie slivovica

Hej-ha! Počuj ostrohy na skale

Každé dieťa v Terchovej ho cíti v kostiach

Ak máš chrbát ohnutý a jarmo ti páli do mäsa

Pozri na hrebeň, bratku: je hneď pred tebou!

Hej! Ha! Naveky!

Jánošík ešte jazdí!

Jánošík ešte jazdí!

Jánošík nikdy nezomrel!

[Outro – spoločný pokrik, dupanie do vetra]

Valaška hore! Srdce v plameňoch!

Hory držia nášho kráľa!

Hej! Hej! Hej!

Vietor vyje cez Vysoké Tatry ako orol, ktorému ukradli mláďatá, a v tom vetre stále letí meno: Jánošík! Juraj Jánošík! Meno, ktoré sa na Slovensku nenosí len v ústach, ale spieva sa, pľuje sa, plače sa ním a prisahá sa naň – meno, ktoré po troch storočiach ešte stále praská ako bič a vytáča krv slobody.

Narodil sa v roku 1688 v malej Terchovej pod krivým vrcholom Rozsutca, kde sa aj skaly nakláňajú, aby počúvali. Najprv pastierik, potom vojak v cisárskej armáde, potom dezertér, keď zistil, že má namieriť mušketu proti vlastným. Habsburské jarmo tlačilo Slovákom krk ako železný golier a uhorskí páni tučneli z potu horských roľníkov. Zákon to volal poriadok. Jánošík to volal lúpež na koňoch.

Tak začal kradnúť späť.

S bandou nie väčšou než svadobčania (osemnásť, dvadsať, najviac dvadsaťpäť chlapov) premenil Karpaty na pevnosť aj súdnu sieň. Útočili v noci, ticho ako padajúci sneh. Na osamelom priesmyku zastavili panský koč, pištole žiarili ako vlčie oči a v okamihu bolo zlato, kožušiny, dukáty preč – ešte pred svitaním rozdané medzi vdovy a siroty. Od chudobných nikdy nebral. Ženy ani kňazov sa nedotkol. Keď vešal pána, vešal ho s úctou: hodvábnym lanom, aby sa krk neodrel.

Dávali mu zázraky, lebo spútaný národ potrebuje zázraky. Hovorí sa, že skákal zo skaly na skalu ako kamzík, že guľky sa menili na vodu pri jeho kožuchu, že raz svojím opaskom zviazal tri borovice a urobil most cez roklinu. Keď ho napokon chytili (zradili ho za tridsať strieborných od falošného kamaráta), smial sa, keď ho viedli na hák. Smial sa! Kat mu v liptovskomikulášskom námestí prebodol rebrá železom a Jánošík tancoval vo vzduchu, krv jasná ako jarabiny, a spieval zbojnícku pesničku, kým mu nezastalo srdce.

Ten smiech je dušou Slovenska.

Tri storočia sa mocní snažili ten smiech zabiť. Habsburskí dôstojníci pálili pesničky. Uhorské žandáre strieľali spevákov. Fašisti vešali nových Jánošíkov na nové háky. Komunisti zavreli legendu do múzea a nazvali ju „triednym vedomím“. Vždy, hory ten smiech vždy vrátili, ešte ostrejší.

Lebo Jánošík nie je človek – je odmietnutie kľačať. Je sekerou, ktorá si pamätá strom. Je pastierom, ktorý sa stal búrkou. V každom námestí stojí jeho socha (valaška naklonená, pištoľa v jednej ruke, druhá otvorená, akoby hovorila: „Ber si, čo je tvoje“). Deti sa učia chodiť tak, že držia jeho kamenné prsty. Starci naň pripíjajú slivovicou a prisahajú, že ho včera v noci videli na hrebeni nad Zázrivou, plášť mu vial vo vetre, kontroloval, či sa bohatí ešte boja.

Nikdy nezískal kráľovstvo. Nikdy nesedel na tróne. Vládol len tri letá a zomrel ako dvadsaťpäťročný s železným hákom v boku. Napriek tomu žiadny cisár, žiadny diktátor, žiadna cudzia armáda neovládla slovenské srdce tak ako on. Lebo ríše plynú ako jarné topenie, ale muž, ktorý okráda zlodeja a dáva okradenému, muž, ktorý sa smeje, kým mu hák trháda mäso – ten muž je naveky.

Počúvaj v zimnú noc v Tatrách. Keď vietor reve dolu z Kriváňa a oheň sa usadí na žeravé uhlíky, začuješ to: slabé cengotanie ostrohov o skalu, tiché zapískanie zbojníckej a potom ten smiech – divoký, vzdorný, nesmrteľný, reže tmou ako čepeľ živého svetla.

Jánošík ešte jazdí.

A pokým bude aspoň jeden Slovák, ktorý si pamätá, aké je to stáť rovno pod ťažkým jarmom, nebude jazdiť sám.